|

By C. Giovanopoulos

The outbreak of the corona pandemic has catapulted the notion and, most importantly, practices of care to the epicenter of societal issues and everyday relations. The state-related responses and management of the epidemiological (turned political) crisis unveiled a crisis on solidarity and care across various lines and scales: from the geopolitical and the infrastructural to the biopolitical and the inter-personal. At the same time, at least in the first months of the pandemic, we have seen a simultaneous globally emergence of mutual-help networks and practices. Grassroots and informal attempts that mushroomed against the neoliberal ‘atomisation’ of responsibility, ‘social distancing’ and lockdowns. Along the line, the latter, in the name of precautionary health-care, proved to be forerunners of a biopolitics that on one hand, normalized practices and/through technologies of surveillance and (further accumulation of) public control, while on the other, it restricted severely the use and notion of public space and social (a precondition to human that is) contact. Both have had serious consequences on the social character of public health-care provision and pro-people policies among others. In this context, the self-organised, bottom-up attempts for social solidarity and care, and also demands and struggles of health-workers, confronted (still do) a new regime of generalized and naturalized (more or less moderate) ‘state of exception’. It seems, more and more, that “we live in a world where … folks are getting in trouble for giving food to the poor, medicine to the sick, water to the thirsty, shelter to the homeless”, as the Pirate Care collective argues. “And yet our heroines care and disobey. They are pirates”, persist in the call for the exhibition “Pirate Care: A Survey of Practices”, that took place in Galeria Nova, Zagreb, between Nov. 27 – Dec. 1, 2021. Pirate care is a collective that “is researching, documenting and facilitating learning from the increasingly present forms of activism at the intersection of “care” and “piracy”” forms that “intervene in one of the most important challenges of our time, that is, the “crisis of care”.”. It approaches care “as a political and collective capacity of societies to attend to the most fundamental needs of humans and their environment (which) is becoming more difficult or criminalised.” In such socio-political state “what defines these practices as pirate care” is that often they appear as, or forced to be, acts of civic disobedience that politicise the notion and practices of care. What’s more the collective has put together an online Pirate Care Syllabus, written in 2019 and 2020 by 14 activists, researchers and artists. Such effort has been the basis for the exhibition which presented contemporary and historical pirate care practices. During the exhibition two seminars/webinars were held focusing on Healthcare As Disobedience. Infrademos was called to participate in the first one, in which it presented the experience of the “Solidarity Clinics in Greece as infrastructures of commoning”. In the same seminar, Valeria Graziano, from Pirate Care, introduced the notion of ‘Healthcare as Dissobedience’ and Pantxo Ramas, also researcher and activist, spoke about “The Legacies of Basaglian Deinstutionalisation of Mental Healthcare”, in Northern Italy during the 1970s. The latter example manifests how collective self-organised and bottom-up attempts for the development of alternative healthcare structures and practices have prefigured changes in and the reform of mental-care institutions and treatment, worldwide. Moreover, one of the basic findings of such endeavor, namely that over 60% of health issues (and diseases) have social –rather than biological- causes, conflates with the most recent experience of the solidarity clinics in Greece. In addition it justifies for the prefigurative role of such self-organised healthcare structures, active in Greece over ten years now, towards/as socialized infrastructures of primary healthcare. In this way, both cases, beyond their ‘pirate’ character, stand paradigmatic of more participatory, inclusive and egalitarian examples of social, institutional and professional (health-practice in this case) transformations. They allow for questioning and reimagining the established settings and standards of healthcare practices and institutions; and they are suggestive of reforms that address not merely human and political agencies, but also the material and immaterial environments and technologies employed in healthcare practices.

4 Comments

During 2021 and 2022 the PI of infra-demos, Dimitris Dalakoglou, is carrying out field-research on the island of Evoia on the contestation of renewable energy infrastructures, together with the project's film-maker Spyros Gerousis. Within the context of the this field-work, infra-demos will publish its third and last documentary film on infrastructures of energy on Evoia island. Below we publish some stills from the film.

infra-demos, in collaboration with the project's informants from 'Save Agrafa' and according to its participatory action research plan, produced the film 'Agrafa Untrodden' on the explosive development of industrial-scale wind turbines projects in the entire country during the lock-down period of COVID-19 pandemic.

'Agrafa Untrodden' is directed and filmed by infra-demos' film-maker, Spyros Gerousis and the activist Giorgos Economou, produced by infra-demos PI, Dimitris Dalakoglou, it features interviews by the activists Anna Iasmi Valianatou and Dimitris Gotsis. By Christos Giovanopoulos i

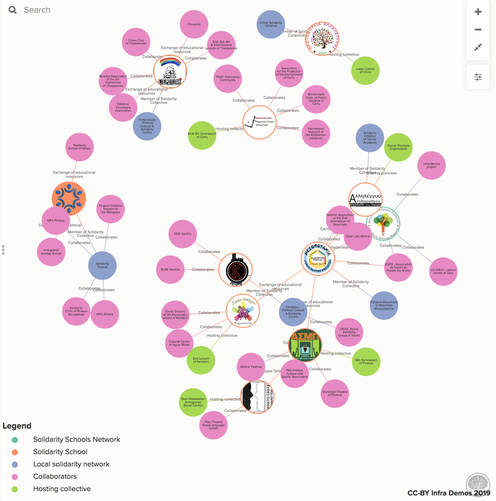

Our map of solidarity schools network in Greece was jut launched. One of the most active and still evolving self-organised solidarity networks among those developed in Greece in the recent years has been that of the solidarity schools. Those voluntary education communities practically provide free tutorials to schoolkids and adults, Greeks and immigrants, who have been deprived of their income, livelihoods and rights. The first initiatives of the kind started long before the crisis to support the needs of the refugee and immigrant communities by offering free Greek language courses. During the crisis this practice inspired other grassroots solidarity initiatives in their efforts to counter the consequences of austerity policies which affected Greek and non-Greek families on the field of education. One of the consequences has been the growing inequalities regarding the entrance to higher education, favoring those students coming from families with super high and high income and cultural capital against those with middle and low ones (IOBE 2019). Thus by organising free tutoring classes when any extra-school-hours support provided by the public school system ceased attempted to maintain some notion of ‘equal chances’ for those students from lower incomes or educational background (Tsikalaki & Kladi-Kokkinou 2016). The solidarity schools launched their network, which continues to develop, in early 2016. At the very same time that other sectors of the solidarity movement (e.g. food networks or healthcare) were loosing steam. Not coincidentally the Solidarity Schools’ Network (SSN) from the outset disassociated its existence from the contingencies of the crisis, unlike other solidarity structures e.g. the social solidarity clinics. Yet, the solidarity schools do share the transformative and transfigurative (Giovanopoulos et al. 2020) processes that have been pointed out about other practices of the solidarity movement in Greece (Arampatzi 2018, Cabot 2016, Kioupkiolis 2016). However, the distinctive characteristics of this network remain unnoticed and overshadowed by other notable examples (e.g. solidarity clinics and food distribution networks). Infra-demos’ interest in solidarity schools lie to their sustainability as social and urban nodes between various solidarity collectives and practices, between institutional and grassroots entities and between autochthonous and immigrant population. In addition, the solidarity schools address inequalities in education while they form self-managed communities that interweave the educational with the solidarity praxis. A synthesis that incubates novel ideas pedagogically but primarily affects popular conceptions about the institution of public education altogether. In this context, the solidarity schools can be perceived as infrastructure that advance both educational commons and contribute towards a more inclusive urban social fabric. By outlining the broader ecosystem of the SSN in an interactive map, infra-demos aims to bring to light some qualitative and quantitative properties of this network and to explore its infrastructural capacities and social histories. Moreover, this digital visualisation of the network comprise a useful tool for the solidarity schools themselves as its data produce a documentation that may inform future decisions. In that sense it acts as a self-management tool. At the same time, it composes a re-presentational medium for the SSN and its school members, which have been actively involved in the design process. Hence, the development of this interactive platform can be considered itself as an act of synergetic infrastructuring. As such, it can provide useful insights to both the workings of the solidarity schools as infrastructures of educational commons and to the act of participatory infrastructuring. What the map shows This collaborative project determined the features and functions of the mapping itself. So the interactive map of the Solidarity Schools’ Network combines information on two levels, a textual and a graphic one. The former regards the quantitative and qualitative data of each solidarity school individually and basic information of the other entities with which they collaborate. The second level involves the charting of the web of relations and types of cooperation between the schools, themselves, and with their collaborators. The two layers of data are visualized simultaneously in the same interface. We have done so by using kumu; an open access and open design digital application. Kumu allows the simultaneous presentations of textual or numerical information with a mapping of the connections between various social actors. Hence the map is split in two areas. A graphic one (on the right) that illustrates the entities of the network and the web of relations among them; and (on the left) a list of information about each organization included on the map. By clicking on the symbol/circle that represents an entity on the graphic side the user activates the information related to the chosen unit on the list side. The interactive graphic side includes five types of actors, each presented by a different colour, according to their roles and position in the network. The solidarity schools and the solidarity schools’ network, as a distinct entity, form the main hubs around which the map unfolds and are represented by their logos. Besides them three more types are distinguished: a. local solidarity networks for which the solidarity school is one of their activities, b. hosting organisations, which denote entities that provide shelter to the solidarity schools, and c. the collaborators, that include the diverse organisations with whom each solidarity school or the network collectively co-operate. Moreover, the type of synergy between two entities is stated by a description next to the threats that connect them on the map. This is an important qualitative feature which points out the span of organisations, relations, activities and resource pooling enabled by the network. On the listing side the collected data include: a. biographical information (start date, address, contact details etc.), b. the kind of educational (or other) solidarity provided and for whom (curricula, type of students, non-educational activities), c. ways to mobilise available resources (types of users’ involvement, facilities, funding policy) and d. the closest synergies each school or the network maintains (organisations, type of collaboration). In addition to those dimensions the data regarding the network as an individual entity include: a. the terms of participation - that state the schools’ common aims and organising model, b. the public events of the network and c. quantitative data regarding the volume of people (e.g. students, teachers) or facilities (classrooms etc.) involved in the activities of the network. How the map was developed Infra-demos follows, among other, a participatory action research (PAR) methodology. The latter has determined the ways in which the mapping process was conceived and executed and the choice to develop the platform as a co-design project between infra-demos’ researchers and (members of) the SSN. One of the main PAR principles has been that the researcher facilitates the participation of the communities involved, which eventually overtake the project [HCCRL, 2011]. Such process besides adhering to the mutualistic and participatory practice of the solidarity schools, it also enables insights on the tensions and potentialities of the infrastructural capacities active in a community. The doctoral research assistant of infra-demos’ project (Christos Giovanopoulos) participated in the coordination meetings of the SSN and engaged to the various actions and decision making processes. After an initial discussion and an outline of the network’s map was presented to the solidarity schools’ coordination assembly a feedback process was initiated. The deliberation, comments and suggestions that were made informed the design and final layout of the platform. The process included data collection through interviews, visualization by the infra-demos’ researchers and presentations for collective assessment and feedback which informed the next phase of the platform’s design. On the whole two rounds of data collection, two targeted discussions in the coordinating meetings of the SSN, two public presentations to solidarity schools’ assemblies and events and a focus groups with members of the SSN that finalized the platform took place. Of course significant remarks were also made during the seventeen semi-structured individual interviews and many informal meetings. Their content exceeded the neat collection of data and embarked into deeper discussions about forms of representation and the understanding of the relation between education, solidarity and infrastructures. Some of the issues raised included: a. the best way to represent the decentralised structure of the SSN and the equal status among the schools, b. what data would be publicly available on the platform, with focus on the quantitative ones and on those related with organisational matters; c. the question about whom does the platform address and what would be its main function for the schools. Preliminary remarks The mapping of the Solidarity Schools’ Network is part of infrademos’ look on solidarity structures as infrastructures of (practices of) commoning in emerging urban settings. As the resulted interactive map illustrates the network expands in various scales and fields: from the local to the international, from meeting educational needs to knowledge sharing and from nurturing structures of urban everyday life to build trans-local affinities. The visualization of the schools’ web of collaborations and the diversity of the actors included provides a glimpse into the resource pooling and the infrastructural capacities of the network. In addition, it reveals the extent to which the solidarity schools’ activities and effects exceed (and problematize) a strict conception of the field of education. As their function and spaces interweave with communal self-organising and with, non-educational, solidarity practices their scope and methods transcend a neat pedagogical perspective when it comes to educational infrastructures. The latter are both expand to and integrated with larger than the ‘into the class’ social contexts, power relations and transformative processes. As such their ‘pedagogical’ role does not regard only the classes they provide but the ‘education in’ and ‘knowledge production of’ a different kind of social organization (Vlachokyriakos, 2017) and shared urban life. It is due to this capacity that the Solidarity Schools Network can be approached as a paradigm of infrastructuring processes of “expanding commons” (Stavrides, 2016) in the era of the ‘networked society’ (Castells 2000). Click here for the link to the Mapping References Arampatzi A. 2018. “Constructing solidarity as resistive and creative agency in austerity Greece” in Comparative European Politics, 16 (1). pp. 50-66. Cabot H. 2016. “‘Contagious’ solidarity: reconfiguring care and citizenship in Greece’s social clinics” in Social Anthropology (2016) 24, 2, pp. 152–166. European Association of Social Anthropologists. Castells M. (2000) The Rise of the Network Society. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Giovanopoulos C., Kalianos Y., Athanasiadis I. N. & Dalakoglou D., 2020 (2020). “Defining and classifying infrastructural contestation: Towards a synergy between anthropology and data science”, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. vol. 554 HCCRL (Healthy City Community Research Lab). 2011. A Short Guide to Community Based Participatory Action Research. Los Angeles: Advancement Project- Healthy City Community Research Lab. Available from: https://hc-v6-static.s3.amazonaws.com/media/resources/tmp/cbpar.pdf [Accessed 26th April 2018] IOBE (Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research). 2019. Εκπαιδευτικές ανισότητες στην Ελλάδα: Πρόσβαση στην τριτοβάθμια εκπαίδευση και επιπτώσεις της κρίσης (Educational inequalities in Greece: Access to higher education and the effects of the crisis) Athens: IOBE Kioupkiolis A. 2016. “The Commons and Hegemony: Alternative politics at the onset of the 21st century” in Kotionis Z. & Barkouta Y. Practices of Urban Solidarity, 2016, pp. 28-35. Volos: University of Thessaly Press Stavrides St. (2016) Common Space: The City as Commons. London. Zed Books Tsikalaki I. & Kladi-Kokkinou M. 2016. “Οικονομική κρίση και κοινωνικές ανισότητες στην εκπαίδευση: Οι εκπαιδευτικές επιλογές των υποψηφίων για την τριτοβάθμια εκπαίδευση” (Economic crisis and inequalities in education: Educational options for students to enter higher education) in ACADEMIA, Number 7, 2016, pp. 34-82, Patras: University of Patras Vlachokyriakos V. et. al. 2017. “HCI, Solidarity Movements and the Solidarity Economy”, in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA -------------- i Christos Giovanopoulos (doctoral research assistant in Anthropology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) carried out the fieldwork, data collection and conceived the SSN’s interactive map which he co-developed within the context of infra-demos VIDI project, under the guidance and supervision of Yannis N. Athanasiadis (Assistant Prof. Wageningen University) and the infra-demos’ Principal Investigator, Dimitris Dalakoglou (Prof. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam).

Wasting the West is the first infra-demos short documentary. It aims to give an ethnographically grounded perspective of the least known part of the wider Athens metropolitan complex: West Attica. Focusing on the Fyli landfill – the only active waste infrastructure in the Attica region— the film describes how the governance of waste goes hand-in-hand with environmental degradation, corporate power and socio-spatial marginalisation (Dalakoglou & Kallianos 2014).

Built around the narration of Tasos Kefalas, a long-standing participant in local grassroots movements, Wasting the West examines the operation and governance of waste infrastructures in Western Attica in relation to the wider political economy and history of contemporary Athenian infrastructural and spatial development (see Dalakoglou & Kallianos 2018). Of interest here are the ways in which pre-existing forms of infrastructure governance play out in times of crisis. The 2008 financial crisis had a significant impact on the maintenance and development of critical infrastructural networks, resulting in an infrastructural gap in western Europe. This video traces the roots of this relationship to the historically uneven spatial development of Attica. The latest so-called ‘golden decade’ of public works (Tarpagos 2010) – between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s – went hand-in-hand with unjust development that led to a crisis continuum in the West. Today, in West Attica, a multiplicity of heavy industrial and infrastructural operations coexist with communities who have limited access to public services and infrastructures. By attending to the social class inequalities and socio-spatial divisions within Attica, Wasting the West, addresses the relationship between modes of (in)visibility and infrastructure within the context of urban governance. Overall, Wasting the West touches upon the ways in which infrastructural dynamics cut across various scales and contexts (Star 1999; Larkin 2013) indicating that it is often through socio-technical systems that power relations and regimes of injustice and inequality are co-shaped and employed (Graham and Marvin 2001; McFarlane and Rutherford 2008). Bibliography Dalakoglou D and Kallianos Y (2014). Infrastructural flows, interruptions and stasis in Athens of the crisis. City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action, 18(4/5), 526-532. Dalakoglou D and Kallianos Y (2018). ‘Eating mountains’ and ‘eating each other’: Disjunctive modernization, infrastructural imaginaries and crisis in Greece. Political Geography, 67, 76-87. Graham S and Marvin S (2001) Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition. London: Routledge. Larkin B (2013) The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology 42: 327–343. McFarlane C and Rutherford J (2008) Political infrastructures: Governing and experiencing the fabric of the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32(2): 363–374. Star SL (1999) The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist 43(3): 377–391. Tarpagos A (2010). “Constructions: From the “golden decade” (1994-2004) to the crisis of over accumulation (2004-2008) and to the collapse (2008-2010) [in Greek]. Theses, 113(1–2), 133–144. Available at: http://www.theseis.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1129 The Municipality of Northern Tzoumerka, in collaboration with the P2P Lab, organised and invited among other scholars and stakeholders infra-demos to the three-day international meeting on agricultural co-design and distributed manufacturing called Tzoumakers: Cultivating Open-Source Agriculture in Tzoumerka.

In three days, farmers, makers, scholars and enthusiasts explored new ways to deploy advanced and traditional technologies for local agriculture, through discussions and the co-creation of four open design tools and solutions. The event took place between 15 and 17 of September 2019 at the Tzoumakers rural makerspace in Kalentzi, Tzoumerka. By Yannis Kallianos infra-demos, Postdoc Researcher In June 2018, thousands of tonnes of garbage were left uncollected in the city of Athens and across the surrounding region of Attica. This waste crisis lasted well over a week from June 9th until June 21st. It was the result of the temporary shut down of Fyli landfill, the only legal waste management facility in the region. According to the governing authorities, the landfill had to shut down due to a major crack created by a series of storms that had swept through the region during that period. The general secretary of Attica’s waste management authorities (EDSNA) explained that an initial ground subsidence, a ‘frequent phenomenon when it comes to landfills’ according to him, had later developed into a major crack because of the heavy rainfall. This is not the first time that heavy rain has been blamed for such destabilizations. Similar incidents occurred in March 2003 as well as in February 2019, and both resulted in the temporary closure of the landfill. In their announcement about the June 2018 crack, waste management authorities portrayed this interruption of normal waste flows as a technical issue that only concerned the experts. Specialized terminology has been purposefully used on many occasions by authorities as a way of classifying the management of waste as a technical issue, thereby eliding the social and political dimensions which are inherent in this process. According to collectives who are active in environmental struggles in the area, and who advocate for the closure of the landfill in Fyli, the actual reason for the cause of cracks and destabilizations has little to do with weather conditions, but instead with the fact that the landfill has reached – and in fact far exceeded – its capacity. Thus waste processing in the available designated areas cannot be properly executed due to limited space, and garbage is being deposited in cells that have already been filled. To accommodate the everyday needs of the capital and sustain the uninterrupted transfer of waste to the landfill, current waste management processes are increasing the risk of destabilization. At issue are the ways in which the long term effects of uneven infrastructural development and environmental injustice play out within the context of governance and contestation in the current period of crisis. Fyli landfill, which is situated at the urban margins of modern Athens, has been used as a dumping site since the 1960s. Since 1991, when Schisto landfill ceased operation, it has been the only active landfill in the Attica region. While it has gone through a series of institutional and technological transformations in order to comply with various EU directives, in reality it is an assemblage of inactive waste dumps, active landfill disposal areas and privatized facilities which operate under concession contracts, all of which are situated only 500 metres away from local residences (see fig 1). This massive landfill has redefined the socio-economic and environmental conditions of the wider area and has shaped the political economy of waste flows and disposal in Attica. The Committee on Petitions of the European Parliament (2014: 16), which made an official visit to the site in September 2013, noted that the ‘degradation of the environment in Fyli will be a monument of environmental mayhem, sickness and human suffering at least for the next three generations living in the area unless something more fundamental is done to restore the area’. Moreover, since the early 1990s, the municipality of Fyli has been receiving the so called αντισταθμιστικά οφέλη, annual offsets provided in order to compensate for the landfill’s environmental effects. Local collectives, however, claim that such environmental counter measures have never actually been implemented. Since there is currently no other legal facility in Attica that could accommodate the region’s garbage, the Fyli landfill continues to operate, and in doing so, generates a series of either short-term or long-term interruptions and crises. We need to examine these crises within the context of both long-term infrastructural and socio-political conditions, and the planning that generates them. In this context particular attention has to be paid to the interrelationship between infrastructure (in)visibility (Star 1999), interruption and normality. While for the majority of the population in Attica and Athens, these infrastructure processes become visible only when the garbage disposal system is temporarily interrupted, for the local population who live near the site the effects of this unjust infrastructural development are experienced daily. Permanent crisis Such waste crises should not be considered extraordinary. To the contrary, they have become more common over the past few years. While in Attica such interruptions are temporary, in other parts of Greece, waste crises have acquired a more permanent status. In many places there have been periods during which garbage was not collected because there was no legal facility in which it could be processed. In most cases, such events occurred because local open dumps, which had been operating illegally, were forced to close down under threat of immense fines by the EU. Pyrgos, a city in the western Peloponnese, was faced with this kind of continuous interruption of garbage collection on several occasions between 2009 and 2015. To deal with the situation, the authorities started using a waste wrapping machine which produces garbage bales. Although the purpose of these machines is to facilitate the temporary storage of garbage, since 2009, the authorities have accumulated almost 100.000 tonnes of garbage in a site located near Alfeios river (see fig 2). The accumulation of such vast amounts of garbage, for such a long period of time, has had devastating effects on the local environment, as well as constituting a serious fire hazard for the entire area (see fig 3).

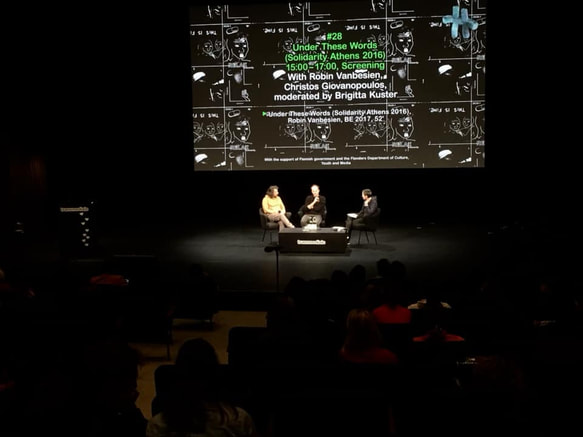

The long-term characteristics of these events reflect a particular type of crisis which does not emerge instantly but rather grows gradually into a permanent situation. This process occurs through the normalization of an infrastructure regime that is organized around an uneven infrastructural development (Dalakoglou and Kallianos 2018). Infrastructural contestation Over the past years, a variety of local community groups and initiatives have started organising around the management of waste. Mobilised by both waste crises and the long-term processes of environmental pollution and urban fragmentation, they have begun to demand transparency around the various official systems of waste disposal and to advocate for public, decentralized infrastructures. While, they have developed within different contexts and have taken on diverse forms, they share common ground in practices which challenge the dominant infrastructural paradigm. A recent example is the March 17th 2019 protest in Volos, a city in central Greece, during which thousands demonstrated against the waste incineration taking place at the AGET-Lafarge cement factory. These political mobilizations constitute part of a broader process of infrastructural contestation that challenges established arrangements around infrastructures and their governance. As such, they indicate that infrastructures are re-emerging as important sites of wider socio-political and environmental struggles in Greece. Bibliography Committee on Petitions (2014) on Fact Finding Mission to Greece from18 to 20 September 2013, concerning waste management in Attica, Peloponnese, Thesprotia and Corfu. Dalakoglou, D. and Kallianos, Y. (2018) ‘Eating mountains’ and ‘eating each other’: Disjunctive modernization, infrastructural imaginaries and crisis in Greece. Political Geography, 67, 76-87. Star, S. L. (1999) The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist 43(3): 377–391. By Christos Giovanopoulos Infra-demos made two important public appearances this month. On the 2nd of February it was hosted by Transmediale, one of the most important arts & digital culture festivals in Europe. And on Saturday 9th it was a quest at the 1st radio programme of ERT, the national Greek broadcaster. In both cases Christos Giovanopoulos, the PhD researcher of Infra-demos, was invited and represented infra-demos talking about the solidarity movement and the research he carries out on solidarity infrastructure in Greece. In Transmediale with ‘Under These Words”, a Athens’ solidarity documentary Transmediale is one of the most renowned annual festival of digital media and visual arts. It started as an offshoot of Berlinale in 1988 aiming to accommodate electronic film and video productions. Since then Transmediale represents the emerging landscape in audio-visual arts and digital media, complementing the more classic program and celebration of the 7th art and the silver screen by Berlinale. This is why it is held as an entry to the later, just one week prior to the main film festival. This year’s Transmedialefocused on ‘Affective Infrastructures’; “on how feelings are made into objects of technological design…” as its program states. The key question the festival asked was: “‘What moves you?’, referring not only to an emotional response but also to the infrastructures and aesthetics that govern how affect becomes mobilized as a political force today”. And more specifically it asked: “What motivates social engagement and how can new forms of care and solidarity be developed and embodied?” Issues that lie at the heart of Infrademos’ research on solidarity infrastructures. Among a variety of exhibitions, screenings, workshops and public debates Robin Vanbesien’s film Under These Words – Solidarity Athens 2016was chosen to be screened and presented in a Q&A session by the director and Christos Giovanopoulos of Infrademos. The latter, both appears in this docu-drama and he assisted in its production. The film follows 3 actors, starting from their reflections on “what is crisis”, as they move in the city of Athens visiting five self-organised solidarity structures. As various solidarity activists talk about their endeavors and struggles, the issue moves from the crisis to the solidarity as a transfigurative response to the former. In that sense, the actors’ initial contemplation on the crisis is replaced by the activists’ concrete efforts to substantiate and envision a world based on solidarity. The ‘thick-research’ that facilitated the creative process of the film-making led Robin Vanbesien, the filmmaker, to publish “Solidarity Poiesis: I will come and steal you”(2017). A booklet which collects activists’ reflections and theorists’ conceptualisations in a quest for an updated notion of solidarity, based on its emergent traits against the historically defined modes and perception of this term. Both the reality on the ground and the concepts that those solidarity practices inform, as they appeared in Greece, was the main focus of the Q&A session that followed the screening of “Under These Words”.In addition, issues regarding the aesthetics and representation politics of solidarity were also raised. The session was chaired by Briggite Kuster, who interrogated Robin Vanbesien and Christos Giovanopoulos. The warming up questions were followed by audience’s interventions that revealed both the potential and emergency of solidarity - as notion and as specific post-crisis and post-capitalist paradigm – against the rise of racism and far right nationalism in Europe. However, it also raised concerns that critically crosscut the concept of solidarity against both the rise of neo-fascism - with its various ethno-tribal underpinnings of the term - and the institutionalized evocations of solidarity by dominant political forces and discourses - which bear the bulk of responsibility in undermining the foundations of solidarity (and social welfare) among the lower classes, local and/or not, leading to their fragmentation and infighting. Interestingly, what occurred from the debate, was the need for a notion of a ‘fighting solidarity’. The sociologists Oosterlynck and Bouchaute (2013) in reviewing the various theoretical approaches to solidarity, make a worth noting claim. They suggest that the only theoretical strand of solidarity, as the term has been firstly negotiated in the 19thcentury, which has not been updated with a modern version in the (late indeed) 20thcentury, has been this of the ‘solidarity as social struggle’ (represented by Marx’s and Weber’s take on solidarity in the 19thcentury). What is striking is not so much that the Greek example of solidarity seems to regenerate a paradigm of this missing concept of a ‘fighting solidarity’. It is rather that the participants in Transmediale’s event highlighted the luck of – and therefore the need for - an updated understanding of solidarity as both a mutual, inclusive and militant social practice against structural, institutional and everyday injustices. The debate was of course informed also by the fears and dystopic future generated by the German (and not only) political context. Which only underlines the importance of emerging participatory infrastructures of a ‘fighting solidarity’ as means and hotbeds of a tangible hope and social vision. ‘Solidarity on the Airwaves’ Thus titled the weekly radio program held by the Social Metropolitan Clinic of Hellinikon (MKIE) each Saturday on the 1st programme of ERT, the national broadcaster of Greece, which hosted infra-demos’ researcher Christos Giovanopoulos on the 9thof February. ERT became known in 2013 when the then pro-Troika and austerity coalition (conservatives, social-democrats and euroleftist) government decided to shut it down, out of the blue. The instant mobilisation and occupation of the broadcaster’s headquarters and main studios, by dozens of thousands of people constitute one of the most remarkable moments of the popular resistance to the imposed neoliberal memoranda in Greece. During this fight, which carried on until the reestablishment of ERT as the national state broadcaster in 2015, both the TV and the radio services of ERT broadcasted under the self-management of their staff. ERT, thus represents also one of the fiercest and innovative infrastructural contestation occurred in Greece the previous years of the crisis. At the same time MKIE was the first solidarity clinic to be set in Athens. It was an offspring of the Syntagma sq. occupation, in the summer of 2011, and the fight, led by the radical left mayor of the area Kortzidis, against the privatisation of the old airport and US military base. In this context the local council provided for free premises previously belonging to the defunct airport to the solidarity clinic, as it also did to other citizen self-organised structures (Dalakoglou, 2017). So the radio-program ‘Solidarity on the Airwaves’ is the outcome of these innovative radicalization of social contestation with emphasis on participation and self-management. Each Saturday at 2 pm the MKIE and the ‘Social Kitchen: The Other Man” produce an hourly program presenting the latest on the solidarity movement and other social struggles. The program hosted Infrademos’ researcher Christos Giovanopoulos and OpenLab researcher Vassilis Vlachokyriakos in a joint presentation of some first research findings with the Oral History Group of MKIE. Infrademos’ interrogation of the infrastructuring capacities of the solidarity structures in Greece, follows a participatory action research method. In this framework it participates, among others, in the Oral History Group of the MKIE; which aims to document the history and experience of the solidarity group in a participatory collective way. This has been a way the assembly of MKIE decided, as a tool to detect and design the future potential of MKIE based on its own knowledge and capacities. In this frame, researchers and MKIE members together composed the questionnaires and all were trained by the Athens’ Oral History group on the technical requirements for oral history interviews and documentation. Hence, during the radio program some first examples of the gathered material was presented in raw format. The extracts were chosen by the two researchers and by Petros Boteas, MKIE activist and producer/presenter of ‘Solidarity on the Airwaves’, and they represented a small example out of 17 interviews taken so far (podcast). The solidarity activists’ interviewees provided beyond their personal trajectories, their opinion on matters such as what constitutes solidarity, hierarchy & horizontal structures of organising, the transformative nature of health practices of the MKIE, the future and the limitations of the solidarity clinics. The whole process, besides representing an example of collective reflection, it underlines the potential embedded in the sociality and habitus produced by the self-organised solidarity structures for participatory infrastructuring and knowledge production. References Dalakoglou, D. (2017) Infrastructural Gap. City vol 20(6) Oosterlynck, Stijn & Van Bouchaute, Bart, 2013, Social Solidarities: The search for solidarity in sociology, Diversiteit & Gemeenschapsvorming (DieGem), retrieved on 13.12.2018 from http://www.solidariteitdiversiteit.be/uploads/docs/bib/00321431_1.pdf Vanbesien, Robin (ed.), 2017, Solidarity Poiesis: I will come and steal you, Berlin: b-books & Ghent: MER & Brussels: SARMA & timely. By Christos Giovanopoulos

Infra-demos was in the ISCTE-IUL 2018 conference titled 'Envisioning sustainable and post-capitalist futures' that was held n Lisbon, between 21 and 23 of November, with the paper “From grassroots solidarity structures to infrastructures of commons” presented by the infra-demos PhD researcher Christos Giovanopoulos. The conference was dedicated to “Social Solidarity Economy and the Commons”, as the frame to imagine and develop post-capitalist forms of sharing, working and living. Among its objectives was to document the diverse “alternatives to the socio-economic status quo” developed through the crisis “by mobilizing endogenous practices, institutions and resources and networking among grassroots initiatives”. It also aimed “to respond to challenges that have arisen from recent research on forms of shared governance between the state, the market and the third sector”. Thus, it hosted contributions by various actors, from academics and researchers to activists and institutional representatives, in order to facilitate interdisciplinary dialogue and debates on cross-national level. Fitting with this framing it welcomed experiences and theoretical contributions “guided by an action research strategy” for movements and policy design on Social Solidarity Economy (SSE) and the Commons. Particular attention was given to issues of community building and the deepening of democratic practices, of shared governance strategies and the management of commons, of participatory governance schemes and grassroots socioeconomic dynamics. The over 60 papers that composed the conference program reflected the wide range of movements, organizing methods, infrastructures, solidarity practices, cooperative economies and institutional formats that have emerged in the recent period. In addition, important networks of the cooperative and social solidarity economies shared their experiences and knowledge produced on the ground in round tables. Among those who provided insights and raised issues and questions regarding the direction of SSE and the Commons, were representatives from the Associaciao Mutualista Montepio, from the Global Ecovillage Network, from Cooperativa Integral Catalana, from P2P Foundation, from the global network RIPESS and from the Catalan cooperative network Coop 57. If anything Infra-demos felt like home in this environment. The novel socio-technical relations, challenges and tensions among various agencies (movements, communities, state and the market) constitute the core field of infra-demos’ interrogation in regard with the participatory infrastructural capacities fostered in such emerging terrain. The input of infrademos in the conference resonated and discussed with other takes on the matter that were focusing on the transfigurative role and potential for sustainability of such post-capitalist alternartives. More precisely the paper of Christos Giovanopoulos focused on the experience of the medicine (collection-redistribution and) re-use campaign of the solidarity clinics in Greece. Based on findings from pilot research on the pharmacy of the Metropolitan Social Clinic of Hellinikon, the paper attempted to outline a. the ways in which solidarity structures constitute alternative social infrastructure and b. the process of commoning fostered by such redistributive practice of medicine. The latter axis touched on the ability of such cooperative practice of medicine sharing as a process of transition from perceiving medicine as a “public good” to understanding it as “common good”. Regarding the former, emphasis was given to the “right to infrastructure” (Corsín Jiménez, 2014) that the solidarity collectives exercise, in combination with their ability to constitute their autonomous subjectivities, spaces and (importantly) mediums (Kioupkiolis, 2016) that enable the development of post-capitalist solidarity economies and processes of commoning. Moreover, by outlining the variety of actors and scales involved in the medicine re-use campaign, which span from individuals and grassroots collectives to institutional entities and from local to national to cross-national levels, the issue of their infrastructural capacity was explored. In this framework the socio-technical relations involved in such infrastructuring endeavor, were examined. One of the findings presented is the correspondence between organizational models (e.g. network society – Castells, 2000) and distributive practices (e.g. P2P, Bauwens-Kostakis, 2017) that have emerged on the digital domain of ICT and the cooperative practices developed by low-fi movements, such as the self-organised solidarity clinics, in the physical realm. This co-relation and synchronicity opens up new avenues of research of transformative practices that develop their own transfigurative social paradigm beyond the transition from corporate capitalism and centralized models to platform capitalism and the “sharing economy”. References Bauwens M. & Kostakis V. (2014). From the Communism of Capital to Capital for the Commons: Towards an Open Co-operativism. TripleC 12(1): 356-361. Castells M. (2000) The Rise of the Network Society. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Corsín Jiménez, A. (2014) The right to infrastructure: a prototype for open source urbanism. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32, 342–362 Kioupkiolis A. (2016) The Commons and Hegemony: Alternative Politics at the Onset of the 21st Century, In: Kotionis Z. & Barkouta Y. (eds). Practices of Urban Solidarity. Volos, University of Thessaly Press, pp. 20-35. By Christos Giovanopoulos, Yannis Kallianos , Dimitris Dalakoglou

In May 2018 took place in the Netherlands Institute of Athens the first seminar of infra-demos.net together with AbdouMaliq Simone, Lila Leontidou and 20m participants we discussed about infrastructural gap and the commons. Below follow some reflections on the discussion. When in 1996 Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder posed the question ‘when is an infrastructure?’, in their article ‘Steps towards an ecology of infrastructure’, they’ paid particular attention to the spatio-temporal aspect of infrastructure, which considers that a socio-political examination of infrastructure should seriously address questions of scale and context in relation to everyday organized practices. With this in mind when we ask what are the features that define the infrastructural gap of our time we should also consider the various scales and the diverse contexts in which such a gap becomes transparent, and thus, the different manners in which this gapis experienced, materialized, perceived and embodied. Seen from this perspective, the diverse ways in which normative understandings of infrastructure have been challenged in times of crisis hold a critical ethnographic value. They reflect how our everyday relation to infrastructure space and services embodies certain ways of making sense of our position in the social field. The following question then emerges: to what extent a break away from established relations of power also implies a completely different kind of infrastructure engagement and participation? The discussion that took place during the InfraDemos seminar touched upon these problematics, and the whenof infrastructure, as a way to approach the various implications and effects of the infrastructural gap in relation to urban governance strategies in times of crisis, and the emergence of a politics of commons intertwined with socio-technical innovation. The infrastructural gap (IG) has been defined as the difficulty of the state and private sector to sustain infrastructural networks (Dalakoglou 2017), a condition which emerged in the West after the rupture of the 2008 crisis. The seminar engaged with this problem and attempted to shed light to the different manners of infrastructural and urban relations that emerge in condition of everyday uncertainty, rupture and change. The discussion that took place during the seminar pointed out two main axes through which this infrastructure condition can be approached. First, infrastructure contestation was examined, mostly in the context of the Greek crisis. Such events of confrontation and challenge indicate that infrastructure space has become an important site of public engagement and participation. Lila Leontidou examined historical and socio-geographical aspects of the infrastructure gap in Greece and argued that the demand for the ‘right to the city’ has played a major role during the mobilizations of infrastructure contestation. These events also exemplify the ways in which political relations of power as well as social biases have been historically embedded in the design and development of infrastructure systems In this context, Leontidou explained how the interweaving of commoning practices, urban space and the reinvention of the city has been brought to the forefront by the infrastructural gap. The infrastructural gap, however, has also been related to novel ways of socio-technical engagement. Dimitris Dalakoglou (2017), by posing the question of how the socio-cultural superstructure can create novel forms of infrastructure, considers these practices to reflect a generalized disobedience in Greece since 2010, which for him, has been codified and expressed through infrastructure. AbdouMalique Simone discussed the multifarious ways in which the interweaving between the technological, the social, the cultural and the discursive plays out in Delhi and Jakarta. For Simone, these everyday practices of urban relationality are mobilized through a constant process of ‘re-calibration’ and ‘measure’, which shapes the urban rhythm. The everyday politics of infrastructure space refer, then, to a relation which is both stable and malleable. These analytical perspectives that touch upon the relation between urban space, contestation, uncertainty, governance, and the commons help us address the problem of what the infrastructural condition entails today. Hence, they provide assistance in order to pose important questions in our attempt to anthropologically examine the infrastructural modalities of the crisisof our time. What kind of new infrastructure arrangements are formed in the context of this infrastructural gap? How does the concept and codification of infrastructure changes when different kinds of civic engagement are being practised and mobilized? We see these questions, which work here as a guide in our exploration of infrastructure, to be in close dialogue with the spatio-temporal dimension of such socio-technical systems. The whenof infrastructure allows us to examine urban relationality across diverse contexts and scales. It offer us a way to look at the (inter)connections and movements but also the interruptions and stasis that co-shape the infrastructure dynamic. References Dalakoglou Dimitris (2017) Infrastructural gap: Commons, state and anthropology. City20(6): 822–831. Star, Susan Leigh, and Karen Ruhleder (1996) Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces. Information Systems Research7(1): 111–134. |

Authorinfra-demos Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed