|

By Christos Giovanopoulos i

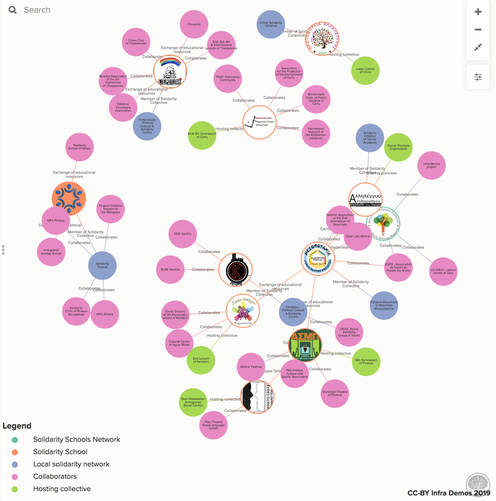

Our map of solidarity schools network in Greece was jut launched. One of the most active and still evolving self-organised solidarity networks among those developed in Greece in the recent years has been that of the solidarity schools. Those voluntary education communities practically provide free tutorials to schoolkids and adults, Greeks and immigrants, who have been deprived of their income, livelihoods and rights. The first initiatives of the kind started long before the crisis to support the needs of the refugee and immigrant communities by offering free Greek language courses. During the crisis this practice inspired other grassroots solidarity initiatives in their efforts to counter the consequences of austerity policies which affected Greek and non-Greek families on the field of education. One of the consequences has been the growing inequalities regarding the entrance to higher education, favoring those students coming from families with super high and high income and cultural capital against those with middle and low ones (IOBE 2019). Thus by organising free tutoring classes when any extra-school-hours support provided by the public school system ceased attempted to maintain some notion of ‘equal chances’ for those students from lower incomes or educational background (Tsikalaki & Kladi-Kokkinou 2016). The solidarity schools launched their network, which continues to develop, in early 2016. At the very same time that other sectors of the solidarity movement (e.g. food networks or healthcare) were loosing steam. Not coincidentally the Solidarity Schools’ Network (SSN) from the outset disassociated its existence from the contingencies of the crisis, unlike other solidarity structures e.g. the social solidarity clinics. Yet, the solidarity schools do share the transformative and transfigurative (Giovanopoulos et al. 2020) processes that have been pointed out about other practices of the solidarity movement in Greece (Arampatzi 2018, Cabot 2016, Kioupkiolis 2016). However, the distinctive characteristics of this network remain unnoticed and overshadowed by other notable examples (e.g. solidarity clinics and food distribution networks). Infra-demos’ interest in solidarity schools lie to their sustainability as social and urban nodes between various solidarity collectives and practices, between institutional and grassroots entities and between autochthonous and immigrant population. In addition, the solidarity schools address inequalities in education while they form self-managed communities that interweave the educational with the solidarity praxis. A synthesis that incubates novel ideas pedagogically but primarily affects popular conceptions about the institution of public education altogether. In this context, the solidarity schools can be perceived as infrastructure that advance both educational commons and contribute towards a more inclusive urban social fabric. By outlining the broader ecosystem of the SSN in an interactive map, infra-demos aims to bring to light some qualitative and quantitative properties of this network and to explore its infrastructural capacities and social histories. Moreover, this digital visualisation of the network comprise a useful tool for the solidarity schools themselves as its data produce a documentation that may inform future decisions. In that sense it acts as a self-management tool. At the same time, it composes a re-presentational medium for the SSN and its school members, which have been actively involved in the design process. Hence, the development of this interactive platform can be considered itself as an act of synergetic infrastructuring. As such, it can provide useful insights to both the workings of the solidarity schools as infrastructures of educational commons and to the act of participatory infrastructuring. What the map shows This collaborative project determined the features and functions of the mapping itself. So the interactive map of the Solidarity Schools’ Network combines information on two levels, a textual and a graphic one. The former regards the quantitative and qualitative data of each solidarity school individually and basic information of the other entities with which they collaborate. The second level involves the charting of the web of relations and types of cooperation between the schools, themselves, and with their collaborators. The two layers of data are visualized simultaneously in the same interface. We have done so by using kumu; an open access and open design digital application. Kumu allows the simultaneous presentations of textual or numerical information with a mapping of the connections between various social actors. Hence the map is split in two areas. A graphic one (on the right) that illustrates the entities of the network and the web of relations among them; and (on the left) a list of information about each organization included on the map. By clicking on the symbol/circle that represents an entity on the graphic side the user activates the information related to the chosen unit on the list side. The interactive graphic side includes five types of actors, each presented by a different colour, according to their roles and position in the network. The solidarity schools and the solidarity schools’ network, as a distinct entity, form the main hubs around which the map unfolds and are represented by their logos. Besides them three more types are distinguished: a. local solidarity networks for which the solidarity school is one of their activities, b. hosting organisations, which denote entities that provide shelter to the solidarity schools, and c. the collaborators, that include the diverse organisations with whom each solidarity school or the network collectively co-operate. Moreover, the type of synergy between two entities is stated by a description next to the threats that connect them on the map. This is an important qualitative feature which points out the span of organisations, relations, activities and resource pooling enabled by the network. On the listing side the collected data include: a. biographical information (start date, address, contact details etc.), b. the kind of educational (or other) solidarity provided and for whom (curricula, type of students, non-educational activities), c. ways to mobilise available resources (types of users’ involvement, facilities, funding policy) and d. the closest synergies each school or the network maintains (organisations, type of collaboration). In addition to those dimensions the data regarding the network as an individual entity include: a. the terms of participation - that state the schools’ common aims and organising model, b. the public events of the network and c. quantitative data regarding the volume of people (e.g. students, teachers) or facilities (classrooms etc.) involved in the activities of the network. How the map was developed Infra-demos follows, among other, a participatory action research (PAR) methodology. The latter has determined the ways in which the mapping process was conceived and executed and the choice to develop the platform as a co-design project between infra-demos’ researchers and (members of) the SSN. One of the main PAR principles has been that the researcher facilitates the participation of the communities involved, which eventually overtake the project [HCCRL, 2011]. Such process besides adhering to the mutualistic and participatory practice of the solidarity schools, it also enables insights on the tensions and potentialities of the infrastructural capacities active in a community. The doctoral research assistant of infra-demos’ project (Christos Giovanopoulos) participated in the coordination meetings of the SSN and engaged to the various actions and decision making processes. After an initial discussion and an outline of the network’s map was presented to the solidarity schools’ coordination assembly a feedback process was initiated. The deliberation, comments and suggestions that were made informed the design and final layout of the platform. The process included data collection through interviews, visualization by the infra-demos’ researchers and presentations for collective assessment and feedback which informed the next phase of the platform’s design. On the whole two rounds of data collection, two targeted discussions in the coordinating meetings of the SSN, two public presentations to solidarity schools’ assemblies and events and a focus groups with members of the SSN that finalized the platform took place. Of course significant remarks were also made during the seventeen semi-structured individual interviews and many informal meetings. Their content exceeded the neat collection of data and embarked into deeper discussions about forms of representation and the understanding of the relation between education, solidarity and infrastructures. Some of the issues raised included: a. the best way to represent the decentralised structure of the SSN and the equal status among the schools, b. what data would be publicly available on the platform, with focus on the quantitative ones and on those related with organisational matters; c. the question about whom does the platform address and what would be its main function for the schools. Preliminary remarks The mapping of the Solidarity Schools’ Network is part of infrademos’ look on solidarity structures as infrastructures of (practices of) commoning in emerging urban settings. As the resulted interactive map illustrates the network expands in various scales and fields: from the local to the international, from meeting educational needs to knowledge sharing and from nurturing structures of urban everyday life to build trans-local affinities. The visualization of the schools’ web of collaborations and the diversity of the actors included provides a glimpse into the resource pooling and the infrastructural capacities of the network. In addition, it reveals the extent to which the solidarity schools’ activities and effects exceed (and problematize) a strict conception of the field of education. As their function and spaces interweave with communal self-organising and with, non-educational, solidarity practices their scope and methods transcend a neat pedagogical perspective when it comes to educational infrastructures. The latter are both expand to and integrated with larger than the ‘into the class’ social contexts, power relations and transformative processes. As such their ‘pedagogical’ role does not regard only the classes they provide but the ‘education in’ and ‘knowledge production of’ a different kind of social organization (Vlachokyriakos, 2017) and shared urban life. It is due to this capacity that the Solidarity Schools Network can be approached as a paradigm of infrastructuring processes of “expanding commons” (Stavrides, 2016) in the era of the ‘networked society’ (Castells 2000). Click here for the link to the Mapping References Arampatzi A. 2018. “Constructing solidarity as resistive and creative agency in austerity Greece” in Comparative European Politics, 16 (1). pp. 50-66. Cabot H. 2016. “‘Contagious’ solidarity: reconfiguring care and citizenship in Greece’s social clinics” in Social Anthropology (2016) 24, 2, pp. 152–166. European Association of Social Anthropologists. Castells M. (2000) The Rise of the Network Society. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Giovanopoulos C., Kalianos Y., Athanasiadis I. N. & Dalakoglou D., 2020 (2020). “Defining and classifying infrastructural contestation: Towards a synergy between anthropology and data science”, IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. vol. 554 HCCRL (Healthy City Community Research Lab). 2011. A Short Guide to Community Based Participatory Action Research. Los Angeles: Advancement Project- Healthy City Community Research Lab. Available from: https://hc-v6-static.s3.amazonaws.com/media/resources/tmp/cbpar.pdf [Accessed 26th April 2018] IOBE (Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research). 2019. Εκπαιδευτικές ανισότητες στην Ελλάδα: Πρόσβαση στην τριτοβάθμια εκπαίδευση και επιπτώσεις της κρίσης (Educational inequalities in Greece: Access to higher education and the effects of the crisis) Athens: IOBE Kioupkiolis A. 2016. “The Commons and Hegemony: Alternative politics at the onset of the 21st century” in Kotionis Z. & Barkouta Y. Practices of Urban Solidarity, 2016, pp. 28-35. Volos: University of Thessaly Press Stavrides St. (2016) Common Space: The City as Commons. London. Zed Books Tsikalaki I. & Kladi-Kokkinou M. 2016. “Οικονομική κρίση και κοινωνικές ανισότητες στην εκπαίδευση: Οι εκπαιδευτικές επιλογές των υποψηφίων για την τριτοβάθμια εκπαίδευση” (Economic crisis and inequalities in education: Educational options for students to enter higher education) in ACADEMIA, Number 7, 2016, pp. 34-82, Patras: University of Patras Vlachokyriakos V. et. al. 2017. “HCI, Solidarity Movements and the Solidarity Economy”, in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA -------------- i Christos Giovanopoulos (doctoral research assistant in Anthropology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) carried out the fieldwork, data collection and conceived the SSN’s interactive map which he co-developed within the context of infra-demos VIDI project, under the guidance and supervision of Yannis N. Athanasiadis (Assistant Prof. Wageningen University) and the infra-demos’ Principal Investigator, Dimitris Dalakoglou (Prof. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam).

3 Comments

12/2/2020 02:17:09

Greece is a place where you can get some top notch education. I know that this is not a popular opinion, but believe me, they do have some great programs there. If you think that it is going to be a huge deal, believe me, it isn't. You need to go and think about what you can and cannot do, or at least that is the thing that you need to be understanding of. I hope that you can do it.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Authorinfra-demos Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed